FASHION FOR A FINITE PLANET

A master’s thesis on the futures of sustainable fashion

Fashion and dress have the power to tell deeply human stories about who we are and who we aspire to be, and their intrinsically social natures can facilitate our search for self-expression and belonging. In tandem with larger global paradigms of economic growth and consumer capitalism, however, what we wear has become increasingly commoditized and destructive to both people and the planet.

Below is a brief summary of the key points of this thesis project.

To read the full report, visit: www.fashionforafiniteplanet.com.

INTRODUCTION & METHODOLOGY

This is a research project that explores the deep systemic issues and impacts caused by the fashion industry’s current reliance on ever faster cycles of clothing consumption and disposal, and what can be done to shift the industry toward a more hopeful, responsible, and sustainable future.

The research question asks how we might change an industry deeply tied to the capitalist system (and with it, perpetual cycles of consumption and disposal) to reclaim fashion and dress as a meaningful tool for expression.

To understand how this change might occur, the Three Horizons Model was used as an analytical framework for the project. Mapped across the axes of fit for purpose and time, the First Horizon (H1) can be equated with the world of “business as usual,” and includes aspects that could be considered broken, but also those worth keeping. The Third Horizon (H3) is the hopeful future – what could come to be if positive change were to occur. The Second Horizon (H2) is the bridge between these two paradigms.

This thesis project aims to understand how change might happen in the garment industry by uncovering the complex and often invisible connections that exist within the system of fashion commerce. In concert with the Three Horizons Model, its six main sections attempt to answer the following questions:

1. Where does systemic resistance to change exist?

2. What's broken now?

3. What's worth keeping from the present?

4. Where is evidence of the future in the now?

5. What's the hopeful future?

6. How might we bridge between paradigms?

1. WHERE DOES RESISTANCE TO CHANGE EXIST WITHIN THE SYSTEM?

Resistance to change within the fashion industry comes in many forms, with much of it driven by wider systems and drivers that pursue endless economic growth – capitalism, globalization, and even the rapid rise of the internet. These forces can be difficult to oppose (or to harness), even for those most dedicated to change.

Explore the report's section on System Archetypes to view more causal loop diagrams relating to the system of fashion commerce.

Within the garment industry itself, fast fashion business models that rely on low prices and perceived obsolescence to drive high levels of consumption have led to hugely profitable business models, meaning more sustainable (and expensive) alternatives can seem difficult to justify.

Design’s deep entwinement with commerce and consumerism can also limit the scope of possibilities considered by designers and entrepreneurs, especially in a competitive environment where bonuses, promotions and awards are often intimately tied to consumption, and where some brands openly admit to designing clothing meant to be worn 10 times or less. Being a small and unconventional voice in the fashion industry is no easy task.

2. WHAT'S BROKEN NOW?

And yet, change must happen. Tragedies like the collapse of Rana Plaza in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where over 1100 lives were lost, are horrific reminders of the exploitation and degradation resulting from the current system of fashion commerce. Simply put, there must be a better way forward.

At a more profound level, many are becoming increasingly concerned with the loss of cultural diversity that has accompanied the modernization (and subsequent homogenization) of global societies. Dress may be but one of many important elements that make up a culture, but it is a signifier of the many ways of being human, that diversity is still alive, and that it has not yet vanished from our memories and consciousness.

The current system is not only harmful to the planet and its workers - it can also be harmful to the people who wear it. Rather than bringing us closer to joy, kinship and beauty, as fashion in its most vital forms can do, fashion commerce deftly manipulates our anxieties and insecurities to incite purchasing behaviour. We consume and consume, and yet are no happier for it.

3. WHAT'S WORTH KEEPING FROM THE PRESENT?

So what’s worth keeping? No culture on earth leaves the body completely unadorned, and in many cases, dress is descendant from ancient realms of ritual, worship and magic. At its best, it can allow us to transcend our bodies to become both an idea and an ideal, and shield us (if only for a moment) from our inevitable mortality.

Dress can provide us with a form of social armour in which to face the world. Historian Elizabeth Wilson describes clothing as “the frontier between the self and the non-self,” and as a powerful tool for communicating identity. There is also great pleasure that can be derived from the tactility, form and creativity of bodily adornment.

4. WHERE IS EVIDENCE OF THE FUTURE IN THE NOW?

This research uncovered many signals that change may be underway – From open criticism of passive consumption, to the desire to live a more mindful, value-driven life, to the blurring of roles between creator and user, signals of a change to the status quo hint at what the new normal could become.

A more expansive collection of signals can be viewed here.

Some companies are already challenging the status quo with innovative business practices and models that aim to balance profit with responsibility. Tonlé, for example, is a Cambodian-based clothing company that uses their zero-waste manufacturing policy to create beautiful, unique clothing and provide meaningful, team-based work to employees.

To see more business models like tonlé's, explore the interactive environmental scan.

Tonlé’s founder, Rachel Faller, estimates that up to 40% of materials that pass through traditional Cambodian garment factories are being wasted. Her business model makes use of these discarded remnant fabrics by giving them new life as hand-crafted garments and accessories, a time-intensive process that can only be done by hand.

5. WHAT'S THE HOPEFUL FUTURE?

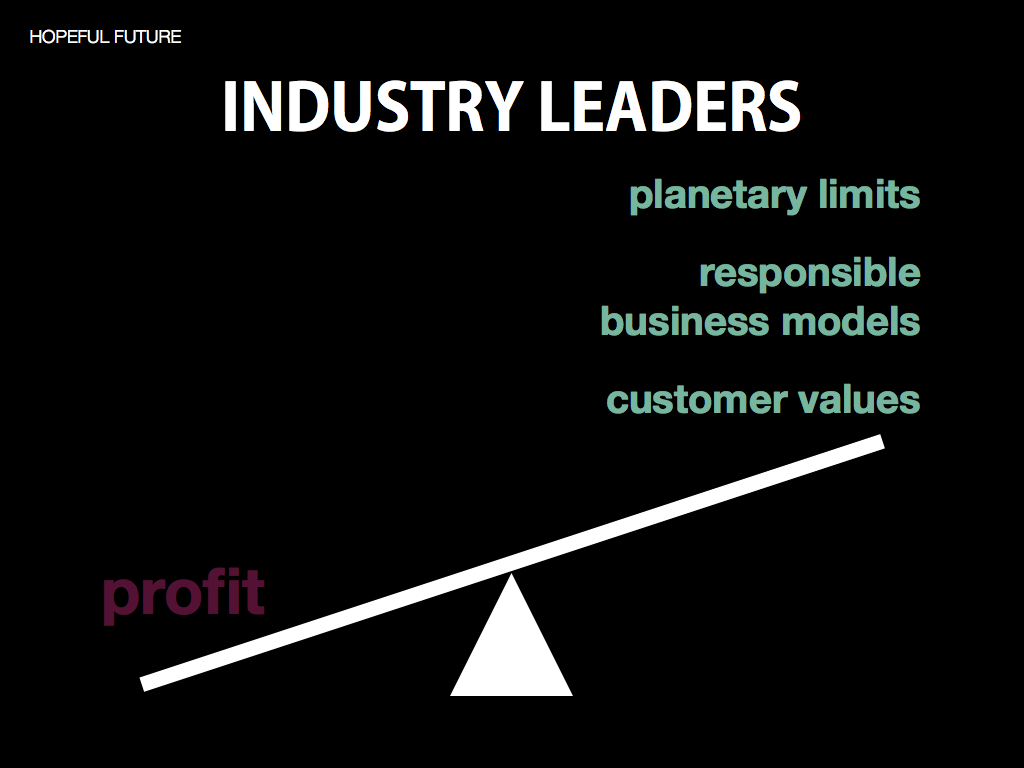

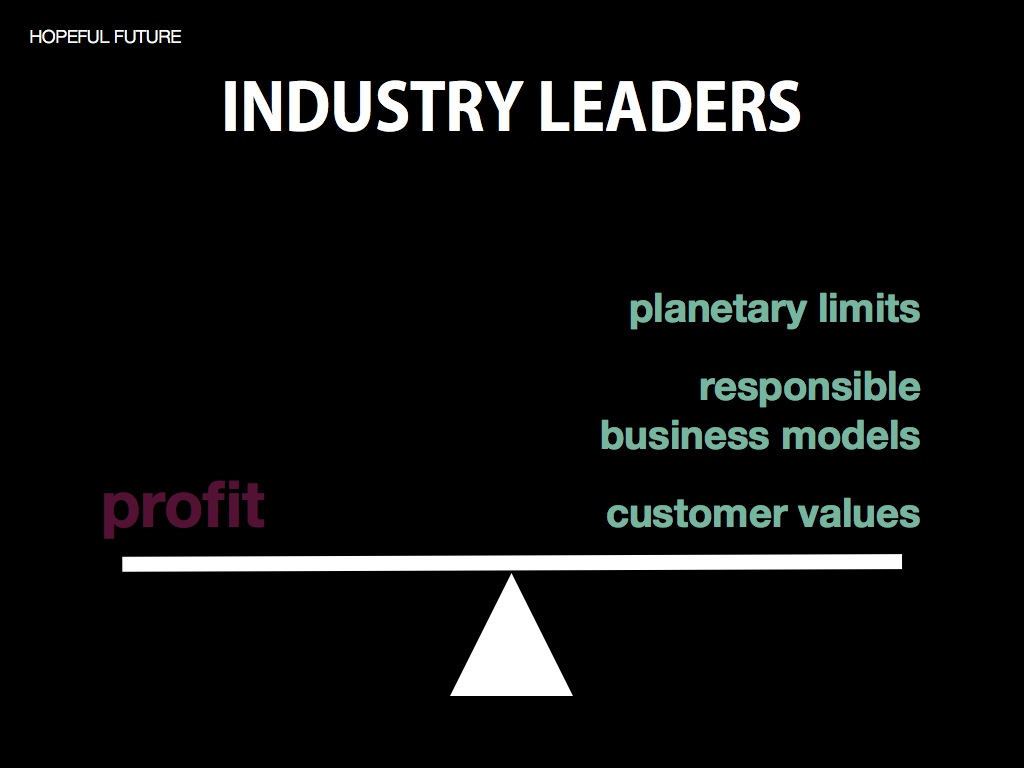

The hopeful future will require industry leaders to balance their need to make a profit with planetary limits, responsible business practices, and shifts in customer values. Importantly, it must also begin to dissociate profit from material throughput, as companies like Patagonia have begun to explore.

Can fashion simultaneously be new and beautiful, celebrate culture, reduce harm, support diverse livelihoods, and remain profitable? Many researchers, advocates and practitioners believe it can, but to achieve it we must broaden our understanding of what fashion and sustainability are, and more importantly, our vision for what they could become. Smaller players have begun to show signs they may lead the way in revolutionizing our economic structures and thinking beyond economies of scale.

The hopeful future might also see individuals reclaim fashion as a tool for meaningful self-expression and identity making. Along with allowing people to play a more participatory role in the creative process of fashion, the hopeful future could also place more control (and therefore responsibility) for sustainability in their hands.

6. HOW MIGHT WE BRIDGE BETWEEN PARADIGMS?

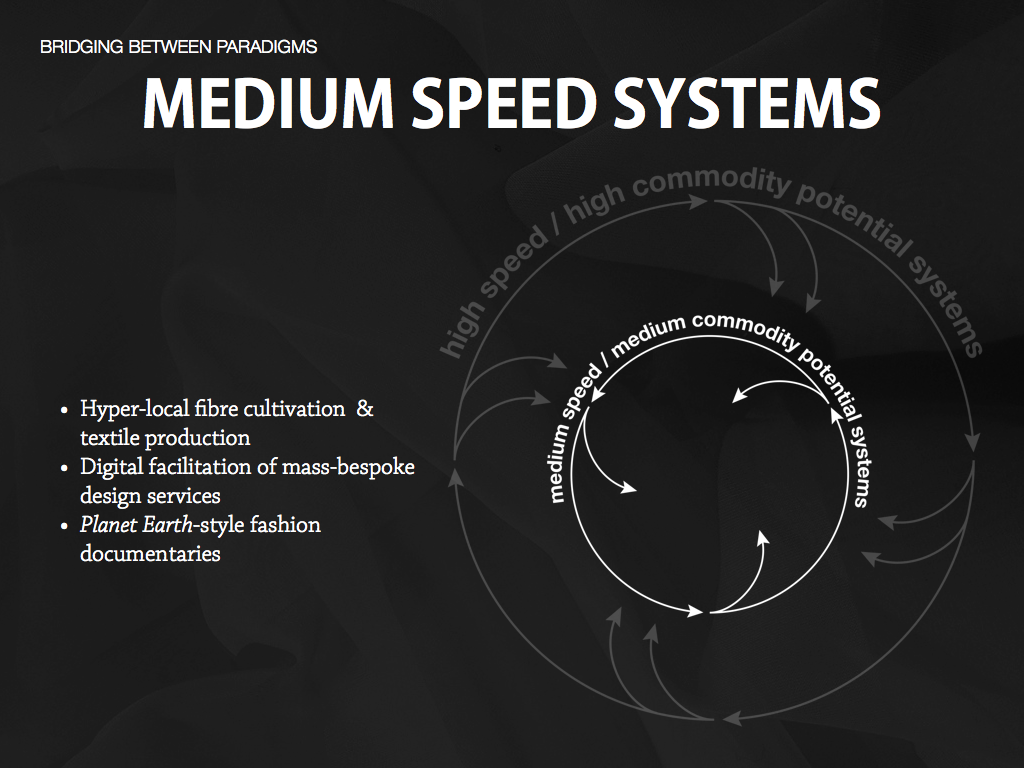

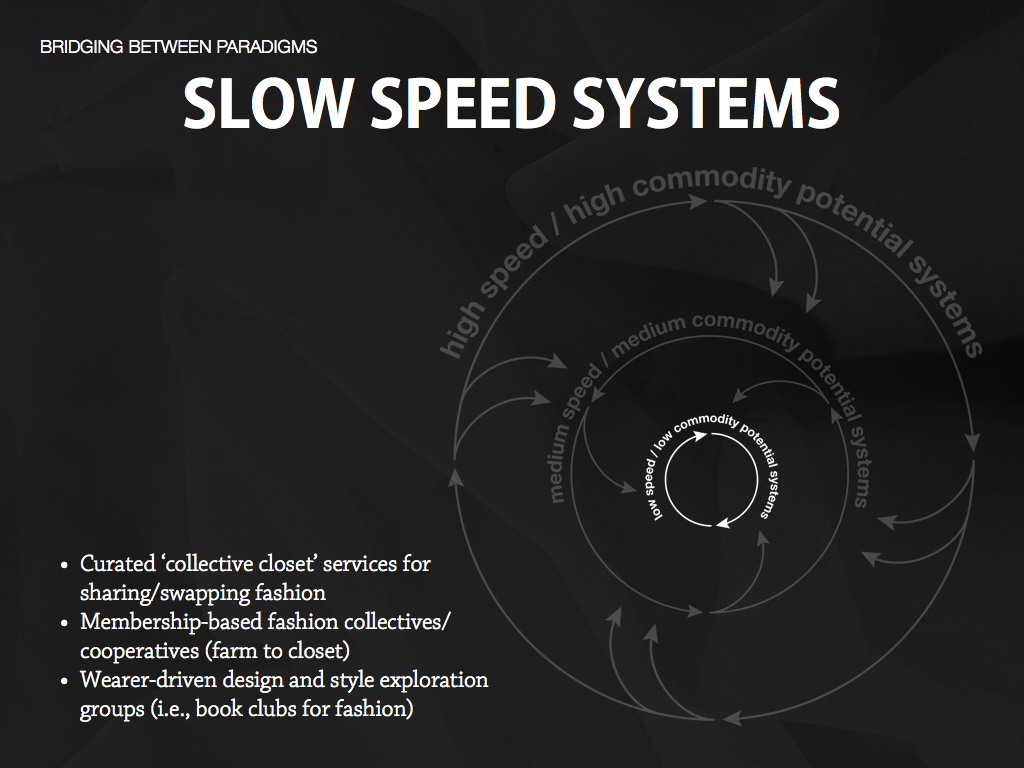

How then, do we bridge between the current paradigm and the hopeful future? One possible way forward might involve re-imagining the role of fast, medium and slow speeds systems that work in concert with one another to serve the greater whole of a sustainable fashion industry.

Fast systems, for example, might involve systems of zero-waste, closed loop textile production.

Medium speed systems might help to facilitate more authentic relationships between the creators, producers and wearers of fashion. This could result in more bespoke and participatory design practices that reflect the unique desires of both designers and individuals.

Meanwhile, slow systems could focus on the truly human elements of fashion – the labours of love that take time to develop and are impossible to replicate at mass scales. That is, activities that embrace the messy, the irrational and the eccentric, the “resolute inefficiency" (Malamud Smith, 2013) of the creative process.

The hopeful future for the garment industry is one that is sustainable, responsible, and beautiful, and like fashion, can take many different forms. Instead of exponential economic growth, we might begin to strive for economic equilibrium. Instead of material throughput, we might focus on cultural throughput in support of art, culture, social connection, beauty and nature. In this type of future, fashion once again become the high expression of humanity it is meant to be.

Completed: 2015

Thesis Advisors: Helen Kerr | Lynda Grose

Awards: 2015 OCAD University Graduate Medal in Strategic Foresight & Innovation

First Place, Graduate Individual, Association of Professional Futurists (APF) 2016 Student Recognition Program